KAUFMAN – Much of this rural community's civic identity comes from the squat, white building on a hill overlooking Route 175 west of town.

Inside the Dallas Crown plant, horseflesh is turned into horsemeat, sold for human consumption in Europe and Asia. About 17,000 horses were slaughtered here in 2004.

The stable-to-table transaction leaves little room for middle ground in the town of 6,600 southeast of Dallas, where the plant has generated controversy since it began processing horses in the 1980s. Many residents accept the plant, which began as a cattle slaughter operation in the 1950s and employs about 50 people, a significant number in such a small town. Others want it closed.

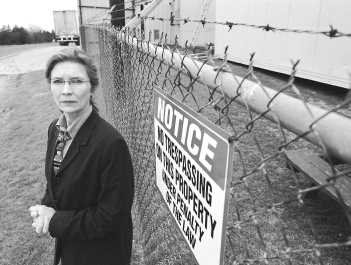

Kaufman Mayor Paula Bacon falls into the second category, calling Dallas Crown "a stigma in our little town."

Responds Kaufman attorney Mark Calabria, who represents the plant: "Dallas Crown has been in business here for a long time. It's a good corporate citizen. We feel the mayor has unfairly singled us out."

For once, Kaufman and Dallas Crown are bystanders in the current debate over a new federal law that would allow wild horses to be sold for slaughter. While Dallas Crown has occasionally accepted individual wild horses, it doesn't expect a notable increase in business.

But that hasn't quieted the public debate in Kaufman about the plant's existence.

Dallas Crown is involved in two pending lawsuits, one challenging a state law and another with the city over sewer usage. The debate over the state law is the more significant legal challenge, which has birthed dueling Web sites.

The root of the matter, both sides agree, is a simple question: Are horses considered livestock or pets?

"Horses are working animals and companion animals," Ms. Bacon said. "They are not a food crop in the United States. It's a huge cultural difference. It's like if you have to be a real grown-up, you have to go out and shoot the yearling."

Fort Worth attorney John Linebarger, who represents Dallas Crown and the Beltex slaughterhouse in Fort Worth, noted that several veterinary organizations support the plants as a humane way of culling the horse population. What happens to horses during the process isn't much different for the cows, pigs and chickens that find their way to supermarket meat counters.

Many Americans simply don't like the thought of Flicka or Trigger on a plate in Paris. And Dallas Crown's Belgian and Danish ownership doesn't elicit much sympathy in Texas.

"There's a cultural difference between us and the Europeans and the Asians," Mr. Linebarger said. "They don't have the same feelings about horsemeat that we do. It's an emotional issue for some groups.

"It would be nice if we could have a retirement home for every horse, dog and cat and none of them would ever have to be put to sleep. But it's just impossible."

A little-known Texas statute dating to 1949 prohibits the slaughter of horses for human consumption. The law gained new prominence in August 2002 when its legality was affirmed by John Cornyn, the attorney general at the time. Opponents of the slaughterhouses hoped to use the law to shut down the two plants.

Soon after, Dallas Crown and Beltex received a temporary injunction in U.S. District Court to stay in business.

Mr. Linebarger argues that Texas doesn't have jurisdiction over interstate and international commerce, which are federal issues. Besides, he says, the state taxes and regulates the horse slaughter industry.

Federal Judge Terry Means has not issued a final ruling in the suit.

Separately, the city of Kaufman has accused Dallas Crown of violating a permit that allows it to discharge extra contaminants into the city's sewer system.

Last year, the city briefly shut off sewer service to the plant, only to have the plant obtain another temporary injunction, this one in state court. While the legal dispute drags on, Dallas Crown continues to operate. The plant says it is in compliance with the permit.

Ms. Bacon said it could cost the city $6 million if it is forced to upgrade the sewer facilities.

"Who in the hell thought it was a good idea to hang an animal slaughter plant on a sewer system designed to accommodate 6,000 people? It's ridiculous," said Mary Nash, whose family has owned land adjacent to Dallas Crown for 150 years.

Kaufman's town square recently featured as many trucks as passenger cars parked around the county courthouse. The Feed Store restaurant, which features pictures of John Wayne and Clint Eastwood from his spaghetti Western days, drew a brisk lunch crowd.

A waitress said the plant's business and accompanying odor are regular topics. Other patrons said that getting a Wal-Mart and a McDonald's are bigger priorities.

Outside the restaurant, two local farmers illustrated opposing views of the slaughterhouse.

"This is a farming community," said Don Burt, who owns a spread outside Kaufman. "People understand how nature works. All animals die. Everything eventually dies.

"It's a humane way to deal with unwanted animals."

Forney-area farmer Jack Phillips said he wouldn't take any of his horses or mules to the plant. He would rather pay to have the animals put down.

"I'm not a big slaughter fan," he said.

The mayor, whose family has operated a local lumberyard since 1896, faces a May re-election challenge. She was once censured by the City Council for her activism. A high school teacher with a master's degree from Harvard and a well-used pickup, Ms. Bacon said most people support her position.

"It's a sad thing for a horse to end up in Kaufman," she said.

E-mail ccarlton@dallasnews.com